Pluralisation of transitions

| Site: | Old Guys Say Yes to Community |

| Course: | Promoting inclusion of older men |

| Book: | Pluralisation of transitions |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Thursday, 26 February 2026, 10:11 AM |

Table of contents

1. Introduction

The transition from employment to retirement has significantly changed in the EU in the last few decades. Not only are years of service extending and the retirement age increasing, but pensions are also falling and they no longer guarantee a decent life. Retirement can be a breaking point in a variety of ways: psychologically, it is seen as a developmental task, as a longer-term process, or a critical life event (Filipp and Olbrich, 1986). Psychologically, the loss of identifying activities points to the loss of self, the loss of worthwhile projects that reflected one’s personality, and also the loss of the meaning of life (Wijngaarden, Leget and Gossensen, 2015). Primarily it can mean a significant cut in people’s biographies (Schmidt-Hertha and Rees, 2017). Despite all the facts and research and with the clear transformations in social life and the increasingly more present re-definitions of gender identity and gender capital, politicians and the wider society still consider that retirement is not a critical life-event or noteworthy change.

Krajnc (2016) acknowledges that building a new

meaning of life is a necessary preparation for a successful transition to

retirement. Forcing older people to a social and psychological “death” after

retirement by not giving them an opportunity to fully experience the new life

situation that they are entering can be devastating for them (Krajnc, 2016). In

a quantitative research study of more than 2,000 interviewees (men and women)

aged between 50 and 69 years from Germany, Schmidt-Hertha and Rees (2017) found

that satisfaction with the workplace in all stages of the career, positive

perception of work and high personal identification with the workplace are

crucial elements on the path to retirement or motivation for delaying

retirement. This can also be seen facing the newly appearing practices of

bridge employment (part-time work before retirement) and re-careering (second

career after legal retirement) (Boveda and Metz, 2016).

2. Silver productivity and ageing

Facing a pluralisation of transitions to the after-working phase of life, including different forms of intermediate stages, educational programmes to design the transition and the stage of life after work, seems to be more relevant than ever (Schmidt-Hertha and Rees, 2017).

Watch the video: How I became an entrepreneur at 66 | Paul Tasner

Watch the video “Paul Tasner – Ted Talk” and think about the importance of experience when considering a new career later in life.

Life expectancy and GDP

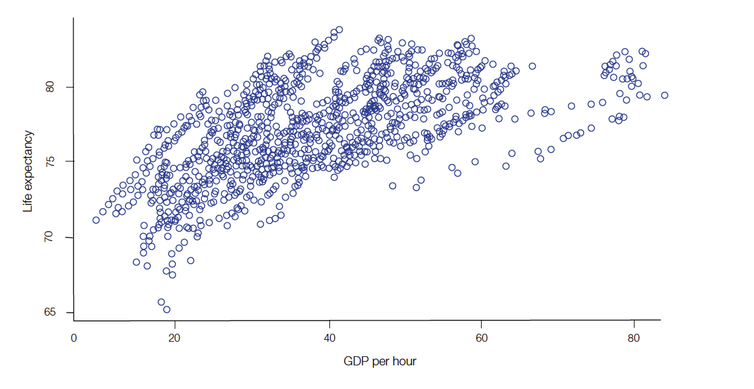

There is more and more evidence in favour of a 'longevity dividend'. Authors of international data from 35 countries published by the International Longevity Centre found that as life expectancy increases, so does “output per hour worked, per worker and per capita”. Mobilising older workers’ skills, expanding labour forces and fostering intergenerational solidarity will mean that rising life expectancy can be both socially and economically good (Flynn, 2018).

Figure 1. Scatterplot of life expectancy and GDP per hour 1970–2015 (35 countries). Toward a longevity dividend, International Longevity Centre (in Flynn, 2018)

3. Post-work lives and identities independent of paid work

Community-based activity, particularly in community men’s sheds, allow men to develop identities independent of paid work. It allows for opportunities for regular social interaction and hands-on activity in groups, within organisations and in the wider community. The value of this interaction was enhanced for older men when this activity was more than individual and cerebral (knowledge or skills-based). It seems particularly powerful, therapeutic and likely to have broader well-being benefits when it is physical and social, involving other men and contributing to the organisation and the community.

This hands-on activity has particularly strong well-being benefits, whether it be via sport, fire and emergency service volunteering, gardening or “doing stuff” in sheds, because it creates, maintains and strengthens men’s post-work lives and identities through communities of men’s practice. In this sense, it allows men to be “blokes” together in ways that are positive and therapeutic rather than negative or hegemonic (Golding, 2011a, 41).

4. Ageing men’s health-related behaviours

This conceptual review summarises the current research on older men and their health-related behaviours with special attention given to the influence of the hegemonic masculinity framework over the life span. The authors consider whether masculinity precepts can be modified to enable men to alter their gendered morbidity/mortality factors and achieve healthier and longer lives. Also included is an overview of the gender-based research and health education efforts to persuade men to adopt more effective health-related behaviours or health practices earlier in the life span.Given the current attention being paid to men’s health, for example, their higher risk of morbidity and mortality both generally and at younger ages, and the associated health care costs tied to those risks, the ethical and economic implications of this review may prove useful (Peak & Gast, 2014, 7).

5. Good practices

Within the project we have identified many good practices. Read their presentations and consider:

- Is there a place in your community where men can meet and participate in various activities (similarly to the Men's Sheds project)? If it does not, do you think that men in your community have enough opportunities to share knowledge and experience? Could a similar project like Men's Sheds be implemented in your community?

- Do you think that you could conduct a "time bank project" in your community? Is a similar project already implemented in your community?

- Find examples of the economic productivity of older adults in your community and find out how these activities affect the wider social sphere.

- Consider where and when the work, knowledge, skills and practices / work of men could benefit and be appreciated by the community during the third and fourth lifetime.

5.1. Exchanging knowledge and experience

In Australia very popular way of informal learning with mainly men communities is taking place in Men's Sheds. These are the places where men meet in order to use one's potential, talents, ideas and to spend time in a productive way. Men get together to fix broken things, build new things, etc., and in order to do so they share their knowledge, experiences, fears and problems with each other. Men's Sheds are mostly represented as one of the best practice for improving men's wellbeing, health and productivity in later life.

Reflect:

Reflect:

Is there a place in your community where men can meet and participate in various activities (similarly to the Men's Sheds project)? If it does not, do you think that men in your community have enough opportunities to share knowledge and experience? Could a similar project like Men's Sheds be implemented in your community?

An example of good practice from Australia: Barry Golding, John McDonald, Małgorzata Malec – Learning by older men in the contemporary adult education research field: some contexts, cases and implications.

See also examples of good practices from Canada; Ireland and Mens' sheds in EU.

Promotion of men sheds in Ireland

5.2. Social responsibility: social time bank

Elderly men are often not activein the community, which is why it is crucial to find good motivation for their greater inclusion. They can use their free time to benefit everyone. One of the ways to do so is Social Time Bank – an informal network of service exchange, where one can offer their knowledge and experience to help others (for example computer classes, language classes, etc.), they share their interests and passions. Participants cooperate with each other, develop attitude of social responsibility, develop social contacts and fulfil the need to be heard and useful.

Do you recognise this idea of Social Time Banks in your community? Would you say something like this is already happening in your community?

Source: Tomasz Schimanek, Social activation of elderly people (Aktywizacja społeczna osób starszych)

Take a look at the example of good practice from Poland: MRS Poznań.

5.3. Positive ageing through productivity and learning

Nowadays we are facing a phenomenon called aging population, because we have more and more elderly people than a few decades ago. These people are often placed on the edge of society and they feel excluded. One way to increase social productivity of older people is by learning. By learning, older people stay active even when their efficiency is lowering, they stay focused on the positive aspects of life, they gain satisfaction from learning and they are still economically productive despite old age.

Reflect:Find examples of the economic productivity practices of older adults in your community and find out how these doings/activities affect the wider social realm.

Source: Renata Konieczna-Woźniak, Learning as a positive aging strategy, 2013

5.4. Needed, recognized and valued: self-esteem development

The elderly have more experience than younger generations, so the interaction between them is desirable. They may know more than younger people about developing and maintaining a vegetable garden – for them to organize workshops to share their knowledge and techniques it means they are developing their self-esteem, the feelings of isolation and loneliness are reducing and they feel like they belong and are useful in their community. These are the main aims of the project called “Horta Solidária” in Portugal.

In Portugal there is yet another group of people of different age, who organize events connected with music and dance. While younger generations usually organize these events, the older generations perform the role of experts, because of their extended knowledge of the music and dance repertory, as well as the cultural traditions.

![]()

Consider where and when older men’s work, knowledge, skills or practices/doings are needed, recognised and/or valued in your community.

Example of good practice from Portugal: Centro Paroquial de Martim Longo, Conjunto Etnográfico de Moldes de Danças e Corais Arouquenses – Rancho de Moldes.

Martins, A. C. (2014). A construção de um lugar de memória: Conjunto Etnográfico de Moldes de Danças e Corais Arouquenses (Dissertação de mestrado não publicada). Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto, Porto.